English teachers will often tell you that the only way to improve your reading comprehension skills is to simply read more. While sound and well-intentioned, this advice probably isn’t very helpful if you must quickly improve your skills, for example earning a higher score on a standardized test like the ISEE, ACT or SAT.

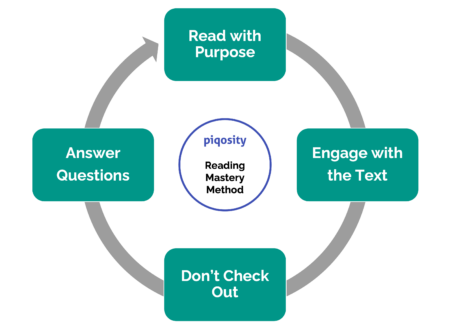

We’re happy to tell you that you don’t need to invent a time machine to go back 10 years just to cram in more reading! Three, simple-to-master techniques to improve your reading comprehension skills right now include:

- Reading with purpose

- Engaging with the text

- Checking in with yourself

Reading with purpose means to go through a passage knowing that you’re going to be asked certain types of questions about it, to be predicting what you’ll be asked.

Engaging with the text means to make both mental and physical notes with annotations.

Not checking out means to maintain awareness that you’ve got a task to complete so you shouldn’t let your mind wander.

If these three strategies seem related it’s because they are, and they’re backed by science! Specifically the psychology of being aware of your own thought processes, metacognition.

If these three strategies seem related it’s because they are, and they’re backed by science! Specifically the psychology of being aware of your own thought processes, metacognition.

In the study “Development of Reading Comprehension in English through Metacognitive Reading Strategies” by Zaily del Toro (2014), specific techniques were highlighted for their effectiveness in improving reading comprehension including predictive reading, summarizing key concepts, and self-questioning (different words for the strategies listed above).

The study demonstrated that when students actively employed these techniques, their comprehension and retention of the material improved significantly.

This research and our 20 years of empirical observation provide a strong argument for incorporating metacognitive strategies into your approach to reading comprehension, particularly for standardized tests.

Reading with Purpose

When you are reading passages for the ACT, SAT, or similar standardized test, you’re not just reading for fun; you are reading because you have to demonstrate your reading comprehension skills by answering mostly standardized questions in a short amount of time.

The keyword here is “time” – for instance, on the ACT, you have approximately 8.5 minutes to read each passage and answer all 10 associated questions. There’s no time to lose! Maximize your time by staying focused on your mission; go in with a plan.

As demonstrated by the increasing popularity of AI-generated articles, most reading passages are pretty formulaic, and the questions that standardized tests ask about them are equally predictable and standardized.

The primary kinds of questions a standardized test is going to ask you about regarding a reading passage include:

- The Main Idea

- Supporting Ideas

- Vocabulary-in-Context

- Tone, Style, and Figurative Language

- Organization and Logic

- Author Intent

Knowing that these are the key buckets, read passages looking for the answers to these questions. This reading with purpose will help you keep pace while actively identifying answers along the way.

Consider Reading the Questions First

Particularly for standardized tests like the new digital SAT that have only one question per passage, reading the questions before the reading the passage is a good strategy to force yourself to read with purpose.

However, don’t spend too much time previewing the questions – think of it as deliberate skimming. Spend just enough time to soak in the types of questions you will be asked, but don’t dwell on them.

Think of this strategy as saving time on test day by not having to read the directions because you already know them from studying ahead of time. If you’re able to study enough in advance such that you can internalize the six buckets outlined above, you probably will not need to read the questions before reading the text (because you already generally know what they’ll be). But if you haven’t been able to internalize these questions, then reading the questions beforehand may be a good strategy for you.

Engaging with the Text

Mark up the reading passage and take notes!

- Underline words or phrases that seem important or appear in the questions;

- Make a star next to parts of the passage you’ll need to look back at later,

- Draw little pictographs next to paragraphs that summarize the main point of the paragraph.

Do whatever helps you keep your thoughts organized.

However, don’t fall into the trap of underlining every single word you read; it takes practice to be able to identify the key words or phrases. To discover what is key, determine which words could be deleted without losing the meat of the sentence. A word either fulfills a syntax purpose, or it provides semantic meaning; if eliminating a word does not cause the sentence to lose its deeper meaning, odds are it is not a keyword.

In addition to marking key phrases and summarizing paragraphs, consider developing a symbol system for quicker note-taking. For instance, use a question mark (?) for parts you find confusing and need to revisit, a star (*) for key points or main ideas, and an arrow (→) to denote cause-and-effect relationships.

Developing your own system and practicing it in your daily reading can significantly improve your speed and comprehension. Start by using these symbols in articles or books you read for leisure. This practice will make it second nature by the time you’re taking your standardized test, allowing for quick and effective note-taking under time constraints.

These engagement strategies are also applicable for increasingly digital tests. Almost every computer-based testing platform includes markup tools for passages.

What is the Author’s Intent?

As you’re engaging with the text and reading with intent, also think about how the passage is organized. There are only a handful of different ways the passages could be structured, and being able to identify them will help keep you laser focused on comprehending the passage. These structures include:

- Chronological

- Compare and Contrast

- Cause and Effect

- Problem and Solution

- Order of Importance

Another way to think about the passage’s organization is through examining the author’s intention. Why did they write this passage? Are they describing something? What, if any, qualitative judgements are they making? Are they arguing a viewpoint? Ask yourself these questions as you read.

Differences Across Genre

You can hone your reading comprehension strategies further by tailoring them for specific genres.

- For Natural Science passages, which often present theories, experiments, or data, focus on understanding scientific concepts and methodologies. Take notes on key scientific terms, experimental procedures, results, and any conclusions drawn. Diagrams or quick sketches can help visualize complex processes or data trends.

- In Social Science passages, focus on understanding arguments, evidence, and the author’s perspective. Here, taking notes on key arguments and evidence is crucial.

- In Humanities passages, which may include topics like history, art, or philosophy, concentrate on the main ideas, historical context, and any arguments or perspectives presented. Your notes should highlight dates, key figures, cultural references, and thematic statements.

- For Prose Fiction or Literary Narrative, it’s important to pay attention to characters, settings, plot developments, and literary devices. Notes should include character descriptions, plot summaries, and notable quotes that reveal themes or character motivations.

Each passage genre benefits from slightly different approaches to note-taking and comprehension. Adapting your strategy to the specific demands of each passage type will significantly improve your efficiency and accuracy in answering questions on standardized tests.

Checking In With Yourself

Have you ever read an entire required-reading passage only to realize you have no idea what you just read after you finished? Don’t fall into this trap; don’t let your mind wander on test day! One of the biggest challenges you’ll face while reading a passage is that you just don’t care about what the author has to say or that it’s boring.

As you finish each paragraph, briefly pause to engage in a quick self-assessment and check-in on your purpose. Ask yourself, “What was the main idea of this paragraph?” and “How does this information relate to the overall text?”

This approach ensures that you are actively processing the information, enhancing your comprehension. Don’t let your eyes glaze over, and don’t ever let yourself read the entire passage without actually taking in a single word.

Again, it’s important not to dwell too long on these self-assessment questions. A quick mental check is sufficient to confirm your understanding or indicate if a re-read is necessary. This habit of self-questioning will keep you engaged and alert throughout the reading process.

Applying Reading Comprehension Strategies to Everyday Reading

This article focuses on how you can quickly improve your reading comprehension on standardized tests like the ACT, SAT, and ISEE. However, the only real difference between passages on a standardized test and more general reading is the length of the text.

Even if you’re just reading online news, you should always be reading critically and thinking about the author’s intent and what ideas they’re trying to convey.

So is your teacher wrong for telling you that the best way to improve your reading is simply to read more? No, not at all. It’s great advice. But that same advice is true for just about everything in life; the more you do something the better you’ll get at it. But there are tried and true steps–like the reading comprehension strategies described above–to get better at something that will accelerate this natural process.

You can improve your reading comprehension skills, and you can do it quickly. Good luck!

References

del Toro, Z. (2014). Development of Reading Comprehension in English through Metacognitive Reading Strategies In Sixth Grade Learners At Institución Educativa José María Córdoba. Revista Palabra, 3, 26-37. Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, DOI: 20.500.11912/6749

More from Piqosity